How Food Recalls Work – A Behind-the-Scenes Look at Distribution Technology

- Protecting customers from further contamination

- Protecting companies from further financial losses

Problems to Be Solved in a Food Recall

First, let’s briefly consider the scope of the egg recall issue. A few of the chief concerns will be:

- Distribution spread – Although the problem originated from a few farms in Iowa, these eggs have been delivered throughout the United States.

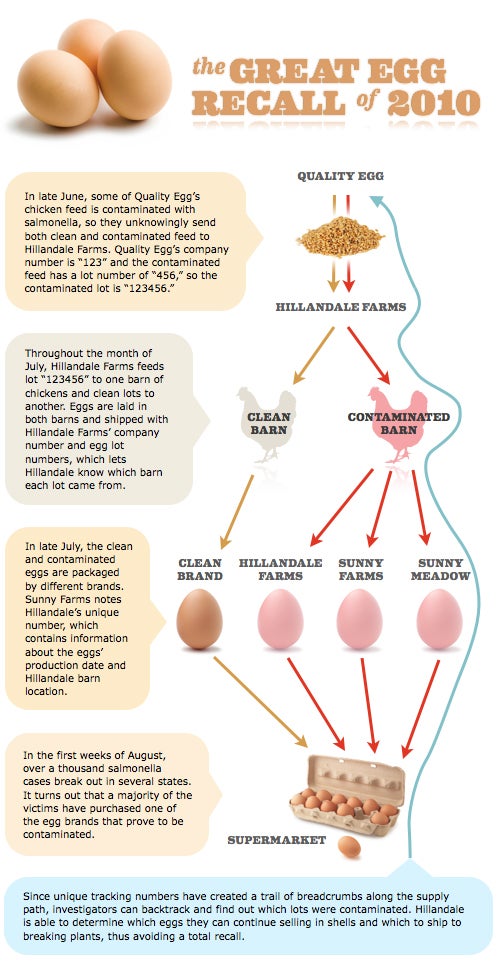

- Packaging confusion – These eggs have been packaged by different brands. For example, Hillandale Farms produced 170 million potentially contaminated eggs and sold them in packages labeled Hillandale Farms, Sunny Farms, or Sunny Meadow.

- Lingering threat of contamination – If more reports of sickness emerge, the recall list could grow. If a new lot of eggs is found to be contaminated, the distributor will need to prepare retailers for more returns.

The key word here is “lot.” According to Chris Anatra, president of NECS, Inc, one of the most useful tools in solving these problems is lot tracking. Lot tracking systems are often provided within food distribution software like NECS’s own entrée, and they are part of a growing emphasis towards traceability in food distribution.

Tracking Down the Source

Soon after eggs are laid, the traceability process begins. Eggs are separated into batches, which are separated further into lots. By assigning eggs to a certain batch, producers can store information about each egg, like the date it was produced, which barn it originated from, and where it was delivered.

For our purposes, we’ll call the contaminated eggs “Batch X.” Let’s say Hillandale Farms has six chicken barns, and Barn X’s chickens are infected with salmonella. So, on Day X, Barn X produces Batch X, which is contaminated. Batch X is then split into several lots, which are packaged as Hillandale Farms, Sunny Farms, or Sunny Meadow and sold all over the country. When Batch X is shipped, a traceability system notes the batch and lot numbers, date and amount shipped, and the receiving customer. With this information, the farm can track the eggs back to the specific barn they came from and determine the production date.

At this point, a farm can send batch quarantine alerts to those who received bad product, which prevents further food poisoning. Producers can also begin backtracking on the supplies sent to them. Both Hillandale Farms and Wright County Egg, another farm that recalled a few hundred million eggs, receive their feed from a supplier called Quality Egg. If both farms received bad feed, Quality Egg can utilize a “where-used” function to immediately seek out other farms that received their contaminated supplies.

In other words, traceability provides “damage control” for a producer like Hillandale Farms in any of the three stages of the supply chain:

- Supplier – If Hillandale Farms traces the contamination back to their supplier, they can shift the blame to Quality Egg.

- Warehouse – Once the farm finds out which batches are contaminated, production from that barn ceases and remaining output is destroyed.

- Customer – Within moments of discovering contaminated batches, the farm can warn retailers to remove contaminated products from their shelves.

The Eggs May Be Contaminated, But That Doesn’t Mean You Can’t Sell Them

Time is of the essence when your customers are being threatened by your own products. However, it is also crucial for the company to continue earning revenue. According to recent reports, both Hillandale Farms and Wright County Farms have stopped distributing their shell eggs to retailers and are now sending them to “breaking plants,” where bacteria is eliminated through pasteurization. This process prevents the eggs from being sold in a shell, but they can still be sold in liquid form, which allows the farms to escape total losses. Ever wonder where that boxed “egg substitute” at the hotel breakfast buffet comes from?

A change like this requires a significant renegotiation of the farms’ transportation contracts, since the eggs must be rerouted to new locations. Whereas Hillandale Farms was previously distributing eggs nationwide using fast, expensive modes of transportation, now the eggs only need to go to nearby breaking plants, allowing the farm to terminate its contracts with coast-to-coast transporters and find cheaper in-state delivery. Farmers can use software to request quotes and solicit competitive bids from transportation providers, assign costs to their lots, and submit contracts to all necessary signers. With the right system in place, farmers will have that egg liquid flowing out and new revenue flowing in.

Should the Government Make Traceability Mandatory?

However, not all farmers are keeping tabs on everything that flows out of their farm. Surprisingly, despite all the recalls in recent years, farmers are not legally required to track their produce. There are many who believe that traceability is the key to preventing worse outbreaks of food poisoning in the future. I spoke about this issue with Dennis Ferrarelli of Produce Pro, Inc., a leading provider of software for the distribution of perishable goods, and he emphasized the importance of planning ahead. In fact, some industry groups are advocating for recall planning guidelines, such as the Produce Traceability Initiative (PTI). The PTI’s ultimate goal is supply chain-wide adoption of electronic traceability for every case of produce by the year 2012.

In order to accomplish this, the PTI has encouraged use of the Global Trade Item Number (GTIN), which would include a company’s unique prefix and reference numbers for the individual product. With such specificity written into each GTIN, companies could pinpoint the contamination source and recall only the affected items, avoiding a disastrous total recall. However, many farmers pass on this opportunity because they are often expected to front the costs related to traceability themselves. By the time a farm has paid for its GS1 Company prefix, installed barcode scanners and printers, and made arrangements to label every case with a barcode, it could be looking at a $200,000 implementation.

Clearly, such expenses would be a major issue for smaller farmers. It would be difficult to ask these small farms, many of whom have been going about their business for years with no safety issues, to suddenly take a huge chunk of their revenue and spend it on technology they don’t want. So, what’s the answer? Could we regulate the larger distributors that are most likely to have difficulties tracking their many products and exempt the smaller farms? Be sure to share your ideas.

Your Privacy Choices

Your Privacy Choices

A small farm can have item level traceability for $280 per year. It is not complicated unless you let someone convince you it is.